It’s Sunday morning and I’m at home, watching a surf movie, waiting for the tide to drop out. Clutching a coffee, my eyes are glued to the screen as the surfer drops down the face of a beautiful head-high wall, snapping off the top, arms relaxed, before cutting back deep into the pocket and speeding down the line. They are backlit, silhouetted, but the fluid lines are seamless, the radical elegance unmistakable, enviable. “Let’s see that wave again.” My boyfriend has wandered into the room and is also instantly mesmerized, watching the person Kelly Slater called, “God’s gift to surfing,” style it out on a twinnie. We are of course watching Steph Gilmore. In 30 minutes of pure surf stoke, she’ll work her way through 12 ‘fun boards’ shaped for her by some of the world’s most interesting, alternative board makers, riding them and reviewing them for the latest edition of the Electric Acid Surfboard Test (Dir. Ashton Goggans). While the best board may be up for debate, one thing is for sure: this is not a guy’s movie, it’s not a girl’s movie, it’s a surf movie pure and simple, and something has changed.

It’s 60 years since Hollywood’s Gidget first brought the beach lifestyle and surf culture to the mainstream consciousness.

It’s 60 years since Hollywood’s Gidget first brought the beach lifestyle and surf culture to the mainstream consciousness. Set against the backdrop of a burgeoning youth culture, the story is based loosely on the real life experiences of a teen surfer, Kathy Kohner Zuckerman, trying to make her way into the scene and into the line up at Malibu in the late 50s – a time when men like Dora, Tubesteak et al ruled the waves. “I couldn’t relate to the girly thing,” recalls Zuckerman. “So when I found Malibu I thought, this is it. I’m going to learn how to surf. I’ve found my place.” While the film may now seem kitsch and outmoded, its attempts to capture the surfing subculture – the language and lore – and it’s wider impact can’t be underestimated. The teen rom-com heralded the start of the surfing boom, which saw literally thousands of would-be wave riders flock to the California coastline, and at the heart of it all was a girl learning to surf on a $35 Mike Doyle board. A year later, Surfer Magazine launched and surf culture in print and in film began to take hold in earnest.

In 1991, all this changed and once again Hollywood was the unlikely source with Point Break. Bear with me. For the wave-riding world this Marmite film is at best a pastiche of the scene – surfers robbing banks to finance an endless summer. While Rolling Stone magazine called it, ‘the greatest female-gaze action movie ever’, this is not about Bodhi or Johnny Utah. Hands down, the coolest and best-defined character was Lori Petti’s Tyler Endicott. She worked a fast-food job to maximize her water time, she ripped, she drove a beat-up Porsche 356 Speedster, and saved Keanu Reeve’s character from drowning, sending him in with the classic line: “You wanna commit suicide, you do it someplace else! This pig-board piece of shit! You got no business out here!” She had attitude and grit, but underneath it had that surf spirit which means you look out for others. The film was directed by Kathryn Bigelow, who’d go on to win an Oscar for Hurt Locker. She delivered us a female surf protagonist with a strong body, a strong mind and a strong character – a female surfer we could believe in and aspire to.

A decade later, spawned by journalist Susan Orlean’s article in Outside Magazine about the ‘Surf Girls of Maui’, Hollywood delivered Blue Crush. This served up a whole raft of strong female surfers on the big screen, from actors to the real deal pros like Sanoe Lake, Coco Ho, Keala Kennely and Rochelle Ballard. As with most mainstream takes on surfing, the merits of the film – equal parts part rom-com and girl power – are debatable, but what’s indisputable is the seismic shift in surfing and the global boom in women taking to the water that resulted. “To be a surfer girl… is perhaps the apogee of all that is cool and wild and modern and sexy and defiant,” wrote Susan Orlean and it captured the zeitgeist. “The Blue Crush phenomenon” was real; surfing and female surfers were everywhere.

Away from the bright lights of Hollywood, Thomas Campbell’s ground-breaking trilogy of ensemble art films, Seedling, Sprout and The Present, released over a decade from 1999, featured the very best of female surfing from the likes of Kassia Meador, Belinda Baggs and Sofia Mulanovich, alongside male counterpoints from Joel Tudor to Alex Knost and Rob Machado. These were not cookie-cutter films with traditional models of representation, they brought to the screen an alternative wave-riding mindset, shining a light on the creativity that exists within surfing, embracing a broad spectrum of board shapes, surfers, locales and styles, and reflecting the changing landscape of the line up. This inclusive, ensemble spirit has been embraced by filmmakers such as Nathan Oldfield.

While ensemble surf movies began to level the playing field, films like Dear & Yonder (2009), directed by Tiffany Campbell and Andria Lessler, reset the stage. This brought together a dynamic all-women cast of all ages, crafts and styles including Linda Benson, Stephanie Gilmore, LeeAnn Curren, Liz Clarke and Kassia Meador, to surf, shape, ride, rip and ultimately traverse perceived boundaries.

Slipstreaming in its wake, the 2010 documentary First Love followed three young female surfers on their journey to making their passion their career. The movie ushered in a new wave of female talent behind and in front of the lens, including current WCT surfer Nikki van Dijk and multi award-winning filmmaking team Clare Plueckhahn and Fran Derham.

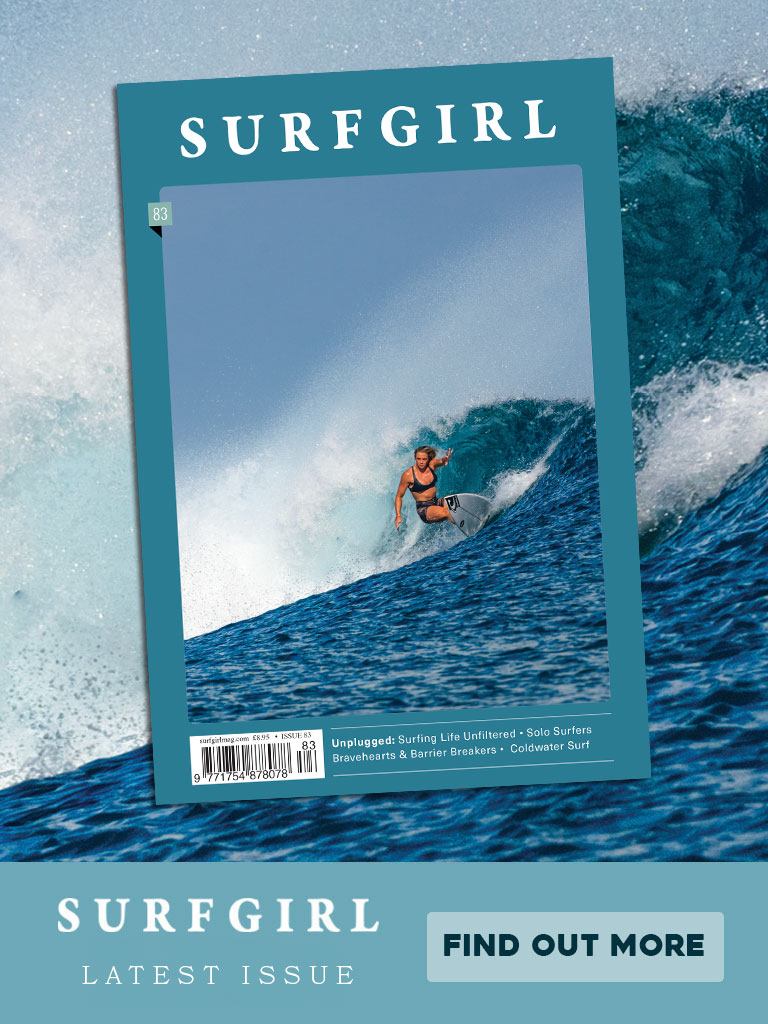

When ‘Leave a Message’ was released in 2011, everyone was ready for it.

When ‘Leave a Message’ was released in 2011, everyone was ready for it. Filmed over two years, featuring the generation’s most radical female performance surfers from Carissa Moore to Lakey Peterson and Laura Enever in the very best waves, and set to a kick ass sound track featuring Paramore to Bloc Party without a ukulele strain in earshot, this genre-breaking ‘parts’ movie elevated female surfing to new levels.

In three short years these three films rewrote the script on what it means to be a female surfer, revealing that there are multiple ways of being and multiple ways of seeing. The rulebook had been torn up.

It’s into this brave new world in 2011 that we founded the London Surf / Film Festival and the last decade has seen a paradigm shift in surf filmmaking and the representation of women on both sides of the camera.

A greater number and percentage of films coming to the fore feature women as a matter of course, reflecting the changes in our line-ups globally and the progression of women’s surfing. With clips dropping all the time of Carissa pulling air reverses or Steph finding new lines on a twinnie, filmmakers can’t justify only featuring men – and why would they? The WSL crew, Carissa, Steph, Lakey and Courtney, rip, and would be the apex surfer in any line up; the likes of Leah Dawson and Kassia Meador are super stylists; LeeAnn Curren and Easkey Britton are acclaimed adventurers; and big wave chargers like Keala Kennelly and Paige Alms are leading the push, so it’s little wonder that it’s these women who feature in the films we screen, or that it’s their stories we want to hear.

Stories of female surfers and communities are being told through groundbreaking documentaries that challenge the status quo and confront gender politics. Award-winning films like Into The Sea (Dir. Marion Poizeau), exploring women surfing in Iran, Surf Girls Jamaica (Dir, Lucy Jane and Joya Berrow), uncovering surfing as a tool for social change, Beyond The Surface (Dir. Crystal Thornburg Homcy), featuring India’s first female surfer, and A Land Shaped by Women (Ann-Flore Marxer & Aline Bock) looking at the role of women in Icelandic society.

Demi Taylor is a writer, filmmaker and Director of London Surf / Film Festival

approachinglines.com londonsurffilmfestival.com

This article appeared previously in SurfGirl 68.